The

Davis' Crossroads site is located at the intersection of

Georgia Highway 193 and Cove Road. The area appears on the

Kensington, Georgia quadrangle of the U. S. Geological Survey

maps.

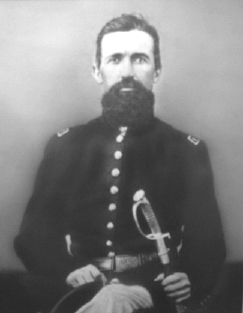

Martin Davis in Indian Removal-era Uniform.

The Davis brothers, Martin and John were from the old Cherokee

area around Dahlonega in Lumpkin County, Georgia. Their

wives, Julia Anne and Saphronia were sisters. Sometime before

1850, the brothers moved to the western part of Walker County

along the Stephen's Gap road that led from Lookout Mountain

to Dug Gap in Pigeon Mountain, and on the LaFayette. John

and Saphronia Davis established a farm on the north side

of the road west of West Chickamauga Creek. Martin and Julia

built their house at the intersection of a north-south road

a short distance to the east. The surrounding farming community

came to be known as Davis' Crossroads.

By 1858, Martin Davis has established a working farm. In

a letter to relatives back at Dahlonega dated March 8, 1858,

he stated: "We have had two bad cases of scarlet fever among

the Negroes ... We are nearly ready to commence crop breaking

our lands for corn. Times in this county are quite hard

and money scarce, plenty to sell but it brings but little."

Martin Davis made an orchard a little to the north of his

house. He spent much time there among the fruit trees, relaxing

and smoking his pipe. In 1859, he was found dead in the

orchard with his pipe still clenched firmly between his

teeth. Because he had loved this spot so well, he was buried

there, thus starting the Davis Cemetery.

When Martin Davis died, his widow Julia was left with six

children, the youngest being two years old. She continued

to direct the slaves in the operation of the farm. The 1860

Agricultural Census showed her to have livestock consisting

of "7 horses, 4 mules, 5 milch cows, 10 other cattle, and

100 swine," valued at $1,400.00. The farm produced 200 bushels

of wheat, 2,000 bushels of corn, and 100 bushels of oats.

The cash value of the farm was indicated at $5,500.00. Julia

also owned 21 Negro slaves. John Davis had a similar farm

with 19 slaves.

The 1860 Federal Census listed Julia Anne Davis as a 37

year-old widow and head of a household consisting of her

children; Jane, 19 years old; Rachel, 17, Mary, 16; John,

13; Thursa, 6; and Martin, 3. On the joining farm to the

west, Julia's brother-in-law, John Davis was listed as a

47 year-old farmer living with his 29 year-old wife, Jane

Saphronia. Their children included: Georgia Ann, 11 years

old; Samuel, 9; Susannah, 7; Daniel, 5; Cicero, 2; and Julia,

a five month-old baby.

During the summer of 1863 there was a strong presence of

Confederate cavalry on the roads around Davis' Crossroads.

By early September, it was generally known that there was

a major Federal army located just on the other side of Lookout

Mountain and they were expected to be crossing at any time.

John Davis felt it advisable to remove most of the more

valuable slaves to a safer place, and did so. On their respective

farms, Saphronia and Julia elected to stay behind on their

property during the expected invasion. At this point, the

three Army Corps that made up the Federal Army of the Cumberland

were separated over a wide area. General Crittenden's 21st

Corps had occupied Chattanooga. General McCook's 20th Corps

was more than 40 miles to the south preparing to move on

Summerville, and possibly Rome, Georgia. General Thomas

was in Lookout Valley with the 14th Corps. From his headquarters

in Chattanooga, the Federal Commander, General Rosecrans,

believed the Confederate army to be in full retreat. He

ordered General Thomas to rush his men through the mountain

gaps and strike the Confederate flank at LaFayette. On September

9, 1863 General James Negley's Division, the first unit

of the 14th Corps, was off the mountain at Bailey's Crossroads

with orders to push through Dug Gap to LaFayette. So far,

the only Confederate resistance that the Federals had met

consisted of token forces of cavalry. Generals Thomas and

Negley, however, had received a number of indications the

Confederates were massing for an attack on the other side

of Pigeon Mountain. In fact the Confederates were fully

aware of the Federal movements, and saw the situation as

an excellent opportunity to destroy Negley's isolated division,

and possibly the rest of Thomas' Corps as they came off

the mountain.

Confederate cavalry general William Martin was the first

to encounter the Federals in Walker County. In the early

morning of September 8, Martin reported that the Federal

advance had forced his troops out of Stevens' and Cooper's

Gaps in Lookout Mountain. Martin withdrew his men to Pigeon

Mountain, the last remaining barrier between the Federal

advance and the main Confederate Army. There, he ordered

his men to fortify and cut down trees to block Blue Bird,

Dug, and Catlett's Gaps. Small bands of cavalrymen also

kept watch on the Federals coming off the mountain and gathering

at Bailey's Crossroads. Although Confederate commander Braxton

Bragg was provided constant information concerning the Federal

movement, he disregarded it until the following day.

On September 9, General Martin sent the 3rd Alabama Cavalry

Regiment into McLemore's Cove to develop the enemy. The

cavalrymen discovered that the Federal unit at Bailey's

Crossroads [Negley's Division] contained between four and

eight thousand men and appeared to be separated from the

rest of the main Federal Army. Later in the day, Martin

informed General Bragg on the findings, adding that the

Federals were moving toward Davis' Crossroads and appeared

to be vulnerable to a surprise Confederate attack. Bragg

was aware that this would be an excellent opportunity to

destroy a significant portion of the enemy army, an accomplishment

that could mean a decisive victory in the campaign. "During

the 9th," General Bragg later wrote, "it was ascertained

that a column, estimated at from 4,000 to 8,000, had crossed

Lookout Mountain into the cove by way of Stevens' and Cooper's

Gaps. Thrown off his guard by our rapid movement, apparently

in retreat, when in reality we had concentrated opposite

his center, and deceived by the information from deserters

and others sent into his lines, the enemy pressed on his

columns to intercept us and thus exposed himself in detail.

Major-General Hindman received verbal instructions on the

9th to prepare his division to move against this force and

was informed that another division from Lieutenant-General

Hill's command at LaFayette, would join him. Written orders

were issued to Generals Hindman and Hill."

Written orders concerning this plan were also issued to

General Hindman by Bragg's adjutant at 11:45 p.m. on the

evening of September 9th. "You will move," the order stated,

"with your division immediately to Davis' Cross-Roads, on

the road from La Fayette to Stevens' Gap. At this point

you will put yourself in communication with the column of

General Hill, ordered to move to the same point, and take

command of the joint forces, or report to the officer commanding

Hill's column according to rank. If in command you will

move upon the enemy reported to be 4,000 or 5,000 strong,

encamped at the foot of Lookout Mountain at Stevens' Gap.

Another column of the enemy is reported to be at Cooper's

Gap; number not known."

At the same time as the orders were sent to General Hindman,

Bragg's adjutant also transmitted written orders to General

D. H. Hill stating: "I enclose orders given to General Hindman.

General Bragg directs that you send or take, as your judgement

dictates, Gleburne's division to unite with General Hindman

at Davis' Cross-Roads to-morrow morning. Hindman starts

at 12 o'clock to-night, and has 13 miles to make. The commander

of the column thus united will move upon the enemy encamped

at the foot of Stevens' Gap, said to be 4,000 or 5,000.

If unforeseen circumstances should prevent your movement,

notify Hindman. A cavalry force should accompany your column.

Hindman has none. Open communications with Hindman with

your cavalry in advance of the junction. He marches on the

road from Dr. Anderson's [at Rock Spring] to Davis' Cross-Roads."

General Thomas Hindman responded promptly to Bragg's orders.

During the night he moved his division through Pigoen Mountain,

and by dawn reached the house of J. J. Morgan, a 43 year-old

farmer living with his wife and nine children on the west

side of Cove Road at the intersection of the road leading

eastward to Catlett's Gap in Pigeon Mountain. Many of the

soldiers got water from nearby West Chickamauga Creek, perhaps

at Gower's Ford a short distance to the north. After a brief

rest, Hindman moved his men further down along Cove Road

and established his headquarters at the H. J. Conley house,

where there was "a spring, the last convenient water before

Davis." Although he was less than four miles north of Davis'

Crossroads, Hindman had not heard from General Hill during

the night, and had received reports of large bodies of Federals

between Stevens' and Dug Gaps. This made him wary, and he

halted in hopes of hearing something from Hill.

General Daniel H. Hill received his orders from Bragg concerning

the joint movement against the Federals at 4:30 a.m. on

September 10. At this late date he realized that the time

factor made the plan impractical and responded with a message

to Bragg explaining why he could not comply with the orders.

General Cleburne, Hill explained had overexerted himself

on the retreat from Tyner, and had been sick in bed. Furthermore,

Cleburne's command was widely scattered. Two thirds of the

division was in LaFayette and the other brigade, commanded

by General S.A.M. Wood, was picketing Catlett's, Dug, and

Blue Bird Gaps. Lastly, it would take hours to clear away

the obstructions in Dug Gap placed there earlier by the

Confederate cavalrymen. Bragg accepted these excuses, and

modified his plan by ordering General Simon Buckner to march

his corps to the defense of Hindman.

General Buckner received an order dated 8 a.m., September

10, from Bragg's adjutant stating: "I enclose orders issued

last night to Generals Hill and Hindman. General Hill has

found it impossible to carry out the part assigned to Cleburne's

division. The general commanding desires that you will execute

without delay the order issued to General Hill. You can

move to Davis' Cross-Roads by the direct road from your

present position at Anderson's, along which General Hindman

has passed."

Captain Milton P. Jarnagin was Judge Advocate in the Military

Court for the Department of East Tennessee attached to General

Buckenr's staff. He left Knoxville with Buckner on August

23, 1863. "Our Dept. court," the captain later wrote, "went

with our commander, Maj. Gen. Buckner, from Knoxville to

Rocky Spring, 9 miles from LaFayette, Ga ... . Gen. Bragg

ordered Buckner's Corps to make a junction with Gen. Hindman

at the mouth or lower end of the cove. This proceeded to

raise a question of rank between them. Hindman had the older

commission. Buckner was an older man, a West Point graduate,

& had the larger force. They wisely agreed to consult and

cooperate. We understood that there were 11,000 [men] in

Buckner's Corps, & 3,000 in Hindman's Division."

"Both

Hindman and Hill were notified," Bragg wrote, "Hindman had

halted his division at Morgan's some 3 or 4 miles from Davis'

Cross-Roads, in the cove, and at this point Buckner joined

him during the afternoon of the 10th. Reports fully confirmed

previous information in regard to the position of the enemy's

forces were received during the 10th, and it became certain

that he was moving his three columns to form a junction

upon us at or near LaFayette. The corps near Colonel Winston's

[McCook] moved on the mountain toward Alpine, a point 20

miles south of us. The one opposite the cove [Thomas] continued

its movement and threw forward its advances to Davis' Cross-Roads,

and Crittenden moved from Chattanooga on the roads to Ringgold

and Lee and Gordon's Mills. To strike these isolated commands

was our obvious policy."

Throughout the day on September 10, General Hindman had

heard the sound of gunfire to the south as Negley led his

division through Davis' Crossroads and up to the mouth of

Dug Gap, skirmishing with the Confederate cavalry all the

way. He could have had his men on the scene in less than

an hour but continued to wait for further orders. After

being joined by Buckner, much time was lost in the discussion

over who would command. The issue was resolved be deciding

upon a joint command. This solution, however, led to each

decision becoming the subject of a lengthy debate between

the two generals. During the night, Hindman sent a message

to Bragg. For some reason, he sent Major James Nocquet,

a Frenchman who claimed extensive service with the French

army in Europe and a position of General Buckner's staff,

but could hardly speak English. The Frenchman explained

to Bragg, in broken English, that Hindman had learned that

Crittenden was moving with a major Federal army upon his

rear. He also felt that the Federal activity in McLemore's

Cove was only a feint, and that the major threat would come

from McCook's Corps at Alpine. In view of these developments,

Hindman felt that Bragg should call off the planned attack.

Nocquet gave a somewhat incoherent account of Hindman's

concerns, adding that he had "heard that the enemy was moving

in a particular direction and [thus] thought it advisable

to modify the orders he had received." General Martin, the

Confederate cavalry commander was present, and he stated

that there was absolutely nothing to Hindman's fears. He

assured Bragg that there were no enemy forces threatening

Hindman's rear, and the major Federal push was definitely

at McLemore's Cove, not Alpine. General Bragg told Nocquet

emphatically that he was to go back and tell Hindman to

attack in the morning, even if he lost his entire command

in doing so.

Bragg then conferred with General Hill concerning Cleburne's

progress at Dug Gap. "Orders were also given," Bragg stated,

"for Walker's Reserve Corps to move promptly and join Cleburne's

division at Dug Gap to unite in the attack. At the same

time, Cleburne was directed to remove all obstructions in

the road in his front, which was promptly done, and by daylight

he was ready to move. The obstructions in Catlett's Gap

were also ordered to be removed, to clear the road in Hindman's

rear. Breckinridge's division (Hill's corps) was kept in

position south of LaFayette, to check any movement the enemy

might make in that direction."

"To

secure more prompt and decided action in the movement ordered

against the enemy's center," Bragg continued, "my headquarters

were removed to LaFayette, where I arrived about 11:30 p.m.

on the 10th, and Lieutenant-General Polk was ordered forward

with his remaining division to Anderson's, so as to cover

Hindman's rear during the operations in the cove. At LaFayette,

I met Major Nocquet, engineer officer on General Buckner's

staff, sent by General Hindman, after a junction of their

commands, to confer with me and suggest a change in the

plan of operations. After hearing the report of this officer,

and obtaining from the active and energetic cavalry commander

in front of our position (Brigadier-General Martin) the

latest information of the enemy's movements and position,

I verbally directed the major to return to General Hindman

and say that my plans could not be changed, and that he

would carry out his orders. At the same time ... written

order were sent by a courier." The written orders instructed

Hindman to attack "and force your way through the enemy

... at the earliest hour that you can see him in the morning.

Cleburne will attack in front the moment your guns are heard."

Two of General Cleburne's Brigades, Woods' Alabama and Deshler's

Texas units, had crawled through, over, or around the trees

blocking Dug Gap, and by morning Cleburne had formed up

for battle within a half mile of the Federal line. A single

ridge separated the opposing forces. Bragg and Hill arrived

to join Cleburne at his position and settled down to wait

for the sound of gunfire that would signal Hindman's flank

attack. "On the morning of the 11th," General Hill later

wrote, "Cleburne's division, followed by Walker's, marched

to Dug Gap. It was understood that Hindman and Buckner would

attack at daylight and these other divisions were to co-operate

with them. The attack, however, did not begin at the hour

designated."

"At

daylight," General Bragg stated, "I proceeded to join Cleburne

at Dug Gap, and found him waiting for the opening of Hindman's

guns to move on the enemy's flank and rear. Most of the

day was spent in this position, waiting in great anxiety

for the attack by Hindman's column. Several couriers and

two staff officers were dispatched at different times urging

him to move with promptness and vigor."

Although it went against his better judgment, General Thomas

followed Rosecrans' plan by ordering Negley to move out

on the morning of September 10 and march through Dug Gap

and on to LaFayette. Thomas did not feel right about this

move, however, and ordered General Baird to hurry over the

mountain with his division to join Negley. Reynolds' and

Brannan's divisions were ordered to follow as rapidly as

possible. Thomas then mounted his horse and, before sunup,

set out to join Negley at the front. "General Negley's [division]

in front of or 1 mile west of Dug Gap," Thomas reported

to Rosecrans' headquarters, "which has been heavily obstructed

by the enemy and occupied by a strong picket line. General

Baird ordered to move up to-night to Negley's support. General

Reynolds to move at daylight to support Baird's left, and

General Brannan to move at 8 a.m. tomorrow to support Reynolds.

Headquarters and General Reynolds' division camped at foot

of the mountain; Brannan's division at Easley's."

The morning was already hot and dusty when Negley's Division

marched out of Bailey's Crossroads toward Dug Gap on September

10. The marching men and officer's horses raised clouds

of dust as they neared Davis' Crossroads. Lieutenant Archibald

Blakely's 78th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment led the way,

moving so fast that they did not bother to deploy skirmishers

in the front. "Personally I do not recollect the events

of any particular day more vividly," J. T. Gibson, historian

of the 78th Pennsylvania Regiment, later wrote, "than I

recollect what occurred on the 10th and 11th of September

in McLemore's Cove. The 10th was a beautiful September day

and our movements through fields and woodlands, along pleasant

ravines, over brooks and ridges, would ordinarily have been

very enjoyable, but there seemed to be something oppressive

in the atmosphere. Soldiers remarked the anxious looks on

the faces of General Thomas and other officers, and, while

the officers did not tell the soldiers of their anxiety,

there was a kind of language without words, so that the

feeling of anxiety was very pervasive."

19th Century View of the Julia Davis House

General Negley, with his mounted staff, rode at the

head of the column. They stopped briefly at the John

Davis house. "We had halted by the wayside," W.S. Brown,

Company A, 18th Ohio Infantry later wrote, "near a Southern

mansion, that of Mrs. [Saphronia] Davis, I think. She

was at home, but Mr. Davis was not anywhere around.

Gen. Negley, with Aids, was sitting on his horse underneath

the shade-trees in the door-yard. He evidently was seeking

information, and politely asked Mrs. Davis how far it

was to LaFayette. She replied with, 'Go and see.' I

think the General blushed a little, but the boys who

heard the conversation knew at once where we were and

what to do. We just helped ourselves to everything good

in sight. After our rest and refreshments we were sent

forward across the creek to reconnoiter."

The Julia Davis House in 2002

|

The advance of the Federal

column had gone about two miles down the dusty, cedar-lined

road when the unexpected happened. "The enemy's pickets

opened fire on us," Colonel Blakely reported. "The division

and brigade commanders, with their staffs, wheeled, rushed

back on us pell mell, yelling 'into line, Colonel; into

line!' Bullets were flying through the cedars thick as

flies and dropping all around us." The 78th Pennsylvania

Regiment pushed slowly forward, skirmishing every foot

of the way. By mid-afternoon the Federal columns broke

free of the cedars to the fields of the widow Davis plantation.

The soldiers deployed into the fields on either side of

the road. From a high knob to the east of the Davis house

they could see the gorge leading to Dug Gap about a thousand

yards away. Within the gap they could clearly see Confederate

infantrymen from Cleburne's division clearing away the

felled trees and rocks that had barricaded the position.

"I left my fence corner by

daylight next morning [the 11th], Captain Jarnagin wrote,

"& rode up the valley, & recognized General Hindman at

a cabin in which he slept the night before. We had known

each other before that. He informed me that orders had

been given to march at sun rise on Davis' X roads, two

or three miles up the cove, where Gen. Thomas with 7,000

men was encamped; that his command was then moving, and

a big noise would soon be heard; that he and Buckenr were

to engage the enemy in the front, and then D. H. Hill,

with 2,000 men, would come down out of Pigeon Mountain,

by Dug Gap, and make an attack in the rear."

To prepare for the attack, General Patton

Anderson formed his division at the Barnes house. Calvin R.

Barnes was a 38 year-old farmer from Tennessee, living with

his wife, Nancy, and six daughters. Also part of the household

was Sam Higgz, a 22 year-old farm laborer from Texas. General

A. P. Stewart formed his division further south, near the

Frick house. General Buckner may have established his headquarters

at the Richard A. Lane house, an imposing structure that was

unfinished because the workmen had returned to New York at

the start of the war. Lane and his family failed to return

after the end of the war.

"At 10 o'clock," Captain Jarnagin stated,

"I was at Buckner and Hindman's Hd. Qurs., some distance in

advance of Hindman's cabin. Lt. Foster of the Engineers, whom

I well knew, rode up, saluted the Generals and said: 'I left

Stevens' Gap within the last 30 minutes. It was entirely clear

and unobstructed. I learned reliably that 400 wagons had passed

through the gap, and were heading towards Alpine, along a

narrow road, so shut in by rocks and woods that it would be

almost impossible for them to turn around.' Gen. Buckner nodded

his head, but said nothing. Just about this time a courier

from Gen. Bate, on the left, towards Pigeon Mountain, reported

the enemy was pressing, so that he wanted re-inforcments."

It was around 4:00 p.m. when the courier returned

with Bragg's message to Buckner and Hindman. "Time is precious,"

the commanding general stated. "The enemy presses from the

north. We must unite or both must retire. The enemy [is] in

small force in line of battle in our front, and we only wait

for your attack."

Davis Ford - Site of Skirmish West of Davis House

"On the 10th of September," Private James

Fenton, Company K, 19th Illinois Infantry, wrote, "Negley's

division reached the open end of the cove and threw up some

slight breastworks, V-shaped, with the point toward the gap.

Heavy skirmishes were going on both sides [of the road] and

at the gap proper ... Our brigade, the 11th Michigan, 18th

Ohio, and 19th Illinois, were moved in to a cornfield. I have

seen descriptions of it in several letters to the National

Tribune. The ears of corn were all above our heads, and although

we expected to go into battle the next minute, some of the

boys took their muskets by the small of the stock and reached

up to touch the tassel with the point of their bayonets. No

one had seen such corn before. Right here was a singular incident.

A man in our front called out in a loud voice, "Boys, where

is General Negley?" And a cavalry man rode out to us from

between the rows of corn, dressed in a fine gray uniform,

a wide gray hat, and on a splendid horse. It was lucky for

him and for us also that we had not seen him before he spoke,

or he would have not lived to warn us. He told our officers

not to go in any farther until he had notified General Negley

that three divisions of Rebel infantry under Hindman, Buckner,

and Walker, were marching to get in our rear by a road on

our left; these troops were ordered to be at our rear by daylight

that morning."

At 10:00 a.m. General Negley reported on

his position. "After passing Bailey's Cross-Roads my skirmishers

were more or less engaged until we arrived at the gorge leading

to Dug Gap, where I halted the command for the purpose of

ascertaining the position of the enemy in the gap. [At} 1:30

p.m., I learned from a Union citizen that a large force of

the enemy (Buckner's Corps), with cavalry and artillery (then

only three miles distant), was approaching toward my left,

from the direction of Cattlet's Gap. I immediately sent one

regiment in the direction of this force, for the double purpose

of a reconnaissance and to compel the enemy to halt, under

the impression that I would attack him. At sundown I made

a strong demonstration in the direction of Dug Gap, driving

the enemy's skirmishers back to his main force and holding

the position until I could establish my picket line un-observed.

Before dark the strongest position of defense the locality

afforded were selected with the intention of bivouacking the

troops for the night, with my trains parked close to my rear.

From the movements of the enemy, and from information obtained

from scouts, I felt confidant the enemy proposed to attack

me in the morning with a superior force. I also learned from

a prisoner, and from Union civilians, that I was confronted

by Hill's Corps of three divisions (twelve brigades), that

Buckner's Corps of two divisions (eight brigades), also Forrest's

division of cavalry, were three miles to my left, and that

Polk's and Breckinridge's commands were in supporting distance.

From the occurrence of testimony on this point, there seemed

no doubt of the fact. I therefore adopted immediate precautionary

measures to guard against surprise. At 9 o'clock in the evening

of the 10th Colonels Stanley and Sirwell were ordered to withdraw

quietly, at 3 the next morning their entire line of pickets

to the west side of the road running along the foot of the

ridge occupied by the enemy, and to remain under arms until

morning. It was subsequently learned that the enemy intended

to surprise my picket line at daybreak, if their positions

had not been changed."

General Thomas fully approved of Negley's

handling of the situation. In a message to General Rosecrans,

he explained why the Federal advance had been halted and his

plans to bring up reinforcements the next day. He pointed

out that Dug Gap "has been heavily obstructed by the enemy,

and which is also occupied by a strong picket line; [Negley]

could not discover what force they have supporting their pickets.

An officer of the Thirty-second Mississippi who was on picket

guard lost his way, came into our pickets and was captured.

He was not very communicative, but was generous enough to

advise General Negley not to advance or he would get severely

whipped. It was also reported to General Negley by citizens

that a large force of the enemy were endeavoring to flank

his position by moving through Catlett"s Gap. Having no cavalry,

he was unable to ascertain whether this report was true or

not, but before I reached his headquarters he had already

disposed his troops to meet an attack on his left flank. I

also ordered General Baird to move to-night with his troops

in his support, leaving his wagons to follow him to-morrow

under a sufficient guard. General Reynolds will also move

at daylight to-morrow to support Baird's left, and Brannan

will move at 8 o'clock to-morrow to support Reynolds. Reynolds

and Brannan will move by the road from Stevens' to Catlett's

Gap ... But one or two divisions of Crittenden's corps, moving

on the road from Chattanooga to LaFayette, would very materially

aid the advance of my corps. I very much regret not having

Wilder's brigade as I believe if I had had it I could have

seized Dug and Catlett's Gaps before the enemy could have

reached these places. The want of cavalry has prevented me

from communicating with General McCook also. I shall move

my headquaraters across the mountain to-morrow with the troops."

The Federal commander took Thomas' news very

badly. One of his aids drafted an immediate reply. "The general

commanding directs me to say," the aid informed Thomas, "that

Negley's dispatch forwarded by you ... is received. He is

disappointed to learn from it that his forces move to-morrow

morning instead of having moved this morning, as they should

have done, this delay imperiling both extremes of the army.

Your movement on LaFayette should be made with the utmost

promptness. You ought not to encumber yourself with your main

supply train. A brigade or two will be sufficient to protect

it. Your advance ought to have threatened LaFayette yesterday

evening."

"It was nearly 11 o'clock," Jarnagin continued,

"when the head of Preston's Division was seen coming in column

on the road leading to Davis X Roads. A courier from Gen.

Bragg arrived just then, and told the Generals that Gen. Bragg

wanted them to attack the enemy at once and in full force,

unless something had happened to make it unadvisable. They

[Hindman and Buckner] said, 'We do not know whether anything

has happened or not.' So they halted Preston, and sent a courier

back around the eastern end of Pigeon Mountain, to inquire

of Bragg the meaning of his order. Then the Generals, and

some staff officers, Col. Ruffin and myself, sat down upon

a long oak log, & waited."

"So imperfect was the communications with

Hindman," General Hill wrote, "That it was noon before he

could be heard from. I was then directed to move with the

divisions of Cleburne and Walker and make a front attack upon

the Yankees. The sharpshooters of Wood's Brigade, under the

gallant Major Hawkins, advanced in handsome style, driving

in the Yankee pickets and skirmishers, and Cleburne's whole

force was advancing on their line of battle when I was halted

by an order from General Bragg. The object was, as supposed,

to wait until Hindman got in the Yankees' rear.

The action made an impression of Private

R. W.Dismore, Company K in the 78th Pennsylvania Infantry

Regiment. "Our Division was in the advance ... " he stated

in a letter to his brother. Our Regiment lost one killed and

four wounded, one of which died since. Company K lost none.

The whole Rebel Army appeared ... against our one division.

The balance of our Corps was back and on another route. I

saw more Rebels than I did at Stones River Battle. We expected

to have a hot time the next morning as the Rebels followed

close to our heels."

Throughout much of the night the Confederate

high command attempted to coordinate Hindman and Buckner for

an early morning attack, as was described in the last section.

At Dug Gap, Cleburne Division was ready. "Passed through Dug

Gap, Pigeon Mountain," W.E. Matthews, 33rd Alabama Infantry

Regiment stated, "in Indian style, one behind the other, crawling

under, around, or over tree logs and brush and logs with high

walls on each side that we could not see in the dark, but

gave the impression that we were in a hole in the ground.

Again passing through the forest on a steep hillside, presuming

there was a deep cut beneath us just to our right ... we descended

into McLemore Cove before day, part of the time under a shell

fire, and came through the same gap in daytime. However, the

obstructions in the road had been moved.

"We were thrown into line of battle," wrote

W. S. Brown, 18th Ohio Infantry, "facing the supposed enemy,

where we lay on our arms all night. We afterward learned that

the whole of Bragg's army was just the other side of Pigeon

Mountain, and that they were busily planning to surround and

capture us in the morning. But we were early. We waited patiently,

peering through the woods in our front."

General Absalom Baird's Division was also

moving throughout the night. "After 3 a.m. on the 11th instant,"

he wrote, "I moved forward ... At about 8 o'clock I reached

General Negley's headquarters at the Widow Davis' house. All

then appeared to be quiet, and I soon after started with him

to ride around his lines ... Returning from this ride, we

were informed that firing had commenced in the front, and

we at once rode to the spot. About half a mile beyond (eastward)

the Widow Davis' house, beyond the woods and with open fields

in front, our line of infantry and artillery was formed, the

right resting upon Dug Gap road, supported by skirmishers

in a wood upon the other side of the road, extending one-fourth

mile farther, as far as Shaw's house. Our main line curved

over the ridge to the Chattanooga road, and thence fell back

to the left and rear, being for the greater part of its extent

in the woods ... In front of our right our line of skirmishers

occupied some woods beyond the open ground, about 800 yards

from our line of battle. Just as we arrived upon the ground

our skirmishers were driven back some 200 yards from the wood

and took shelter behind a fence. The enemy had the advantage

and his fire was quite sharp, but indicated nothing serious."

"My brigade," General John C. Stockweather,

of Baird's Division, wrote, "composed of the 21st Wisc. 24th

Ill. Vols. and the 4th Indiana Battery (79th Pa. Vols. being

to the rear working mountain road), moved forward from this

point at 3 a.m. on 11th inst., together with Col. Scribner's

Brigade, to the support of Genl. Negley's Division which was

five miles in the advance. I reported to him at 8 a.m. having

been obliged to skirmish the whole distance, Col. Scribner's

Brigade being in rear of train. Found his troops under arms

and ready to move in any direction necessary, stacked arms

in an open field and cooked breakfast. Immediately heavy skirmish

firing commenced with Genl. Negley's troops that had moved

in advance into a reconnoitering position -- sent train to

the rear and formed line of battle and was then ordered to

move forward and take position occupied by a portion of Genl.

Negley's Division which was soon to be retired. After occupying

the point designated (Battery being in center, 1st Wis. on

the right, 21st Wis. on left in the woods two hundred yards

to the rear, 24th Ill. To the rear of and acting as support

to the Battery) the pickets and skirmishers to the front were

found to be retiring, as ordered, amid heavy firing from the

enemy. I therefore moved my skirmishers to the front quickly

for their support and for the purpose of taking their position,

protecting them in the movement by the artillery. This was

accomplished without accident. Skirmishing now commenced in

great earnest and continued until 3:30 p.m. when a retrograde

movement was commenced and I was ordered to cover the retreat

of the troops with my Brigade.

"A brisk fire was now kept up all along the

line," Colonel B. F. Scribner later wrote, "the enemy pressing

us with much spirit and vigor. My hay fever was now upon me

again, to my great discomfort. I wore dark goggles to protect

my eyes, and the glare of the light without them was unendurable.

My horse disturbed a hornet's nest in front of my line and

became unmanageable, and so slashed me about in the underbrush

that my glasses were lost. Overwhelmed with a disaster which

would have completely disabled me, I called to my men with

much earnestness to find them for me, which they soon did,

to my great relief. The men tell this incident with great

relish, that I 'stopped the fight to find my spectacles.'"

"At eleven o'clock skirmishing commenced,"

Surgeon S. Marks, 10th Wisconsin Infantry, stated. "I met

Surgeon H. W. Boyce, 11th Wisconsin Volunteers, surgeon-in-chief

of General Negley's division, and we established the hospital

for two divisions at a Mrs. Davis's house, within three-quarters

of a mile of our front, and had received some eight or ten

wounded, when we discovered that our forces were falling back,

and that our batteries were being planted around the house,

making it unsafe for hospital purposes. We at once loaded

them in ambulances, and went back to the foot of Lookout Mountain,

and established our hospitals at a Mr. Stephens's house, where

we cared for the wounded as best we could up to the 16th."

The Confederate threat was such that Negley

felt his position to be hopeless. Because his forces were

on "a long, low ridge, covered with a heavy growth of young

timber, descending abruptly on the north end to the Chickamauga,

while the east, south, and west sides were skirted by corn

fields and commanded by higher ridges, demonstrated the fact

that it would be impossible to hold this or any other position

south of Bailey's Cross-Roads and fight a battle without involving

the certain destruction of the trains ... The preservation

of the trains, perhaps the safety of the entire command, demanded

that I should retire to Bailey's Cross-Roads, 2 miles northwest

of our position ... and that General Baird should hold Widow

Davis' Cross-roads until I could withdraw a portion of the

Second Division and take position on the north side of Chickamauga

Creek."

As the fighting drew closer, Julia Davis

put her children in the fruit cellar under the south end of

the house. She then returned to the house and got her family

Bible. On the porch, she had a word for some of the Federals

before going back to the cellar. "As we were falling back

with the Confederate army as close after us as it was safe

for them to come, we passed a small, but neat little frame

house. One of our Batteries was firing at advancing enemy,

and one of their guns was firing at us. A shell from the enemy's

gun struck the corner of the house, and exploding, tore out

the end of the building. A tall, and rather nice looking lady

came out with a large Bible under her arm, and said to the

boys in blue: 'I hope, gentlemen, you will be highly entertained

today, and I am glad to say the prospect for it is exceedingly

bright,' and she hurried on toward a place of safety."

"There was a field to our left," W. S. Brown,

18th Ohio Infantry, stated, "with thick underbrush in the

woods beyond. Our skirmishers were thrown some distance forward

along the fence on the opposite side of the field. Suddenly

a long line of skirmishers appeared, closely followed by a

line-of-battle. Our boys gave them a warm reception, but when

they had to fall back across the field, they had to run some

distance exposed to a heavy fire from the enemy. We were ordered

to move out, as the rebs were closing in on us from three

sides. The general had ordered a new line of battle on the

rise of ground just north of Chickamauga, and it ran right

through the [John] Davis yard. There was a stone wall on the

roadside just north of the creek, and the 19th Ill. Was lying

behind it, for the rebel cavalry could be seen preparing for

a charge. They did not see the trap, so on they came with

a yell. Just as they got opposite the stone wall the 19th

boys sprang up, as by magic, and one long sheet of flame leaped

from their Springfields. There was a seething mass for a moment,

and then a hasty retreat. It was one of the best things the

19th boys ever did."

"Our men were holding their fire," Private

Fenton continued, "until the Rebels got nearer, when a Rebel

officer on horseback dashed ahead of his line in pursuit of

two Yankees who had been left on the firing line and with

his revolver pointed, said 'Surrender, you Yankee _____ __

_______!' They were the last words he ever said, as horse

and rider went to the ground. Both platoons gave them a volley,

and they quit yelling and fell back from our front."

"I slowly withdrew my command," General Starkweather

stated, "a distance of five hundred yards to the north and

south cross road (maintaining the while with my skirmishers

the same relative position) and reformed line of battle. Troops

of Genl. Negley had in the meantime crossed the west Chickamauga

Creek, and formed a second line of battle. After Col. Scribner's

Brigade had also withdrawn I again retired by the right of

companies to the rear, having sent my battery first across

the creek. My skirmishers were then being heavily pressed,

but as stubbornly resisted and kept the enemy in check until

the infantry had crossed the creek and reformed line of battle.

Skirmishers quickly followed, and formed in favorable and

protected positions. At this juncture the enemy were moving

rapidly on us with heavy skirmishing lines, supported by two

lines of battle cheering as they advanced. I again quickly

retired to top of [a] small hill where I found my Battery

in position, four guns being on the road and two guns to the

extreme right, supported by Col. Stanley's Brigade, when I

again formed line of battle in support of Battery and opened

fire with the same with shell and cannister; the enemy being

received at the same time with a tremendous fire from my skirmishers

(as also the skirmishers of Col. Stanley) were immediately

checked with heavy loss.

"Meanwhile, our line was forming hastily for

the next onset," W. S. Brown, 18th Ohio Infantry, stated.

"While we are moving left in front to the support of our battery,

just west of the house, the rebs coming from the west ran

up a battery and commenced shelling us with bad effect. As

soon as we got to our place in the line we lay down, as the

storm had turned to grape and canister. It got too hot for

our battery boys, and they left their guns for a time, resuming

the fight whenever there was a lull in the storm."

It was after 4 p.m., with little daylight

left, when a courier from General Bragg reached the Confederate

right where General Hindman had placed the divisions of Generals

Anderson, Stewart, and Preston that had been ready to attack

all afternoon. "The attack which was ordered at daybreak,"

Bragg's brief message stated, "must be made at once or it

will be too late." Finally, with dusk fast approaching, Hindman

ordered his men to attack.

Anderson's division, followed by Stewart,

arrived in time to be shelled by one of Negley's batteries,

but were too late to engage the retreating Federal infantry.

With darkness coming on, Hindman ordered Anderson to stop

the attack. "An hour before sundown," General Hill reported,

"I was ordered once more to advance, but the Yankees now rapidly

retired. Their rear was gallant attacked by a company of our

cavalry, but made a stand on the other side of Chickamauga

Creek, under cover of a battery of artillery. Semple'' magnificent

battery was ordered up, and in a short time silenced the Yankee

fire with heavy loss, and the Yankee rout was complete."

|

"The

bluff in front of Company A was soon covered with Rebel troops

and a battery was planted there that shelled our reserve infilading

fire, drove the 18th Ohio out of their works in disorder,

and the whole line was ordered to fall back. Company A was

in a perilous position, but managed to fall back from the

willows with some loss. Negley's division moved back to the

foot of the mountain and threw up temporary works. The enemy

did not follow. Why, we never knew. They had sprung their

trap and it did not work." (30)

Captain Jarnagin was with Buckner when Hindman made his abortive

attack at the end of the day. Preston's [Anderson's] div.

went forward," he later wrote, "the woods were shelled; and

soon it was discovered that Thomas, with all of his wagons

had gone safely through Stevens' Gap; and that his artillery

was shelling the Cove. Missiles fell in the camp ground where

Thomas stayed the night before. Some of our men ran out of

the little houses, one of whom sat behind a tree and examined

his New Testament. Before reaching the crossroads I had met

Capt. Isaac Shelby, of Buckner's staff, who said a great blunder

has been made, which will carry a great responsibility. So

I thought. I had ridden toward Dug Gap a short distance from

the crossroads, when I came upon Genl. Bragg & D. H. Hill

As Gen. Buckner approached, Gen. Bragg sternly demanded of

him -- 'Gen. Buckner, where are the enemy?' He replied 'They

have escaped through Stevens' Gap.' It was then almost dark.

If Thomas had been captured, the blood of 20,000 men would

not have been shed at Chickamauga.

The Federal soldiers constructed breastworks and dug rifle

pits along a low ridge in front of the Rogers' farm at Bailey's

Crossroads. They expected another Confederate attack, but

none came. The remaining two divisions of the 14th Army Corps

joined them there with General Thomas, and the command remained

in the area for a few days. A number of reconnaissance patrols

found that the gaps in Pigeon Mountain were still guarded

by Confederate infantry from Cleburne's Division.

On September 12, the 87th Indiana Infantry Regiment came over

Lookout Mountain. "We crossed the mountain," Peter Keegan,

a member of the unit wrote in his diary, "which is two miles

wide, and descended and went into camp mile from the base.

Water is plentiful where we are camped. At 2 p.m. we moved

to the front without baggage, 3 miles close to Bluebird Gap,

or Dug Gap, where Gen. Negley had a fight with the rebs. 4

of Negley's men lay dead there unburied. We buried them. He

being obliged to fall back to protect his train which he did.

The rebel cav. tried to flank him & destroy his train. His

entire loss I did not learn. We returned to camp at 8 a.m.

The road was very dusty. We marched during the day 15 miles

or more. The land on Lookout is tolerable good. The timber

is heavy and of good quality. There are some fine farms under

cultivation. I should think it would be a good place for fruit,

also Irish potatoes. The soil is of a stiff nature, yet alluvial

enough for good cultivation."

The Federals received information that there was a Confederate

force gathering around the small mill that Dr. John Lee owned

on a branch of West Chickamauga Creek. "On Wednesday September

15th Van Derveer's brigade moved to a position in front of

Lee's Mill and nearer Chickamauga Creek," Jeremiah Donahower,

2nd Minnesota Infantry, wrote, "where the enemy could see

our camp fires, and as a battle was imminent, the regimental

camps were located with a view to quick formation into lines

of battle."

On September 16," Donahower continued, "I was sent to establish

a line of pickets at skirmishers distance of five paces between

them, and to cover the front of the brigade, with company

E and a detail of fifty men from the other nine companies,

with instructions to make the reserve post at Major [John]

Davis' house which stood near the road leading to the creek.

I learned from Mrs. Davis that her husband the Major, on learning

of the approach of Negley's troops, had prudently removed

his most valuable personal property from the large farm and

across the creek and under the protecting folds of the Stars

and Bars, where his numerous slaves would be beyond the reach

of Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation, which was natural, and

a consistent thing to do by a man who believed in the system

of involuntary servitude, but I could not reconcile his precautions

with his lack of care for the safety and welfare of his wife,

an intelligent and handsome woman, and his three very pretty

and interesting children, girls, and one old Mammy, a negress

about seventy years of age, whom he left in the house and

to the care of the despised Yankee soldiers."

Donahower had a lengthy talk with Saphronia Davis that day.

"Mrs. Davis, in answer to my rap on her door," he wrote, "opened

it, and I informed her that we would occupy her front porch,

and that no one would intrude, and that she was quite safe

from harm so far as we were concerned, and when bed time came

to fear no evil, and at the same time I advised her to go

into the cellar if the Confederates began shooting at us,

and there she and her sweet little girls would be out of harms

way. Mrs. Davis was a lady and a very frank one, and from

what she told me I felt sure she lived in fear of evil to

her children and herself, that fear based on the stories told

her by the major himself of the barbarity of the yankee and

of his cruelty and horrible treatment of Southern women so

unfortunate as to fall into his hands, and after she had told

me the stories, she looked into my face and in her face I

read her faith in her husband's love, and especially faith

in his veracity, and that face seemed to say to me -- there,

now I have told you all -- but it did not say to me -- now

murder me if you will."

"But

she was a lady," he continued, "and as I stood humbly before

her with my cap in hand, beneath it all I saw she was not

afraid of us and had not uttered one word of fear or contempt

for the Union soldier other than the stories told her by her

husband of others cruelties. Mrs. Davis talked about President

Lincoln, about the emancipation of the slaves, and in somewhat

pathetic vein on the probable confiscation of their large

tract of land, and I felt that she was in distress over the

possible loss of the latter, and I pitied her, and said, 'Madam,

President Lincoln is a kind and a tender hearted man, be comforted,

he is not the rude and boorish man your newspapers pictured

him, but a big brained and wise man, with a noble soul in

his awkward body, and he will not take your land from you,

but he will punish the South by subduing it, and will give,

nay, has given, freedom to the slaves, and your thirty five

or more slaves will soon be thanking God for Abraham Lincoln.'

I again said to Mrs. Davis, 'Your husband certainly does love

you and your children, and that being so, had he believed

the stories he told you, he would assuredly have taken you

across the river first, and after seeing you safely there,

then have returned for his slaves, and if these three little

girls were mine, I would let all the slaves in our country

go free and hold on to my children.' Mrs. Davis did shed a

few tears, but was greatly comforted with the hope held out

to her that her 1,600 or 1,800 acres of land would not be

taken from her."

"During

the night," he concluded, "two of my detail in violation of

orders went to the front to dig a few potatoes in a field

in a bend in the creek and were made prisoners of war, one

of the two dying while a prisoner. On the morning of the 16th,

I had questioned Mrs. Davis as to her treatment by the men

of Negley's and Baird's divisions, and her reply was that

personally she had been treated with respect, but that the

soldiers there two days before our arrival had gone into the

cellar and had taken away all of her food -- everything that

could be eaten. Later I rode over to Genl. Brannan's division

headquarters and made Mrs. Davis' cause known and he promised

to send her some coffee and other supplies from his own stores.

The very same men guilty of taking Mrs. Davis' potatoes, jam,

hams &c., would, in the home of the poor and the hungry, empty

their own haversacks of coffee, crackers and bacon and freely

give it, and the sick and the wounded never appealed to them

in vain. The night of the 16th passed with no demonstration

by the enemy, but Van Derveer's brigade was in line in readiness

for attack."

"We

could see the Rebs signal Corps on a hill close to us for

two days," R. W. Dinsmore wrote in a letter to his brother

on September 16. "We have since received reinforcements. The

21st Corps [actually General McCook's 20th Corps] came over

the mountain today. I have just now received orders to have

my company ready to move with two days rations at 3 o'clock

in the morning. The whole division is to move at that time.

We expect to have a rough time."

"On

the 17th troops," Jeremiah Donahower stated, "probably the

advance division of Genl. McCook's Corps, which had been ordered

to march from Alpine ... McCook began his march from Alpine

on the night of September 13, crossing the mountain at Winston

Gap and descending through Stevens' Gap. Up to this time Rosecrans

had acted on the offensive, but on the arrival of McCook in

McLemore Cove on the 17th he changed his attitude to one of

defense. More or less minor conflicts had occurred, and Bragg's

change from threatening attack on Thomas and McCoook to concentrating

against Crittenden's Corps, and the knowledge that he was

receiving reinforcements from Virginia revealed Bragg's strategy,

and let General Rosecrans to make the change and look after

the safety of his left and of the roads that led to Chattanooga."

General Thomas moved his men further north as McCook's men

arrived, and established headquarters for the 14th Army Corps

at Pond Springs. The Confederate infantry in the gaps on Pigeon

Mountain also moved out, being replaced by General Joseph

Wheeler's cavalry. "On Thursday evening, 17th instant," Colonel

Thomas J. Harriison, 39th Indiana Mounted Infantry Regiment,

reported, "I was ordered with my regiment to Bailey's Cross-Roads,

in McLemore's Cove, which is opposite and 2 miles from Dug

Gap and 3 miles from Blue Bird Gap. Those gaps were occupied

at the time by a strong force of the enemy. About 3 p.m. my

regiment was attacked by a brigade of rebel cavalry at Davis'

Ford, on Chickamauga Creek. The fight lasted two hours. The

field was left in our possession ... On the next day, we skirmished

at the Widow Davis' Cross-roads, retaining the ground without

loss."

Following the Chickamauga and Chattanooga campaigns, the main

war moved further south. Nevertheless, there was still considerable

hostility and hardship in the local area. On March 6, 1864,

Mary Davis, the daughter of Julia Anne, started a letter to

her aunt, Susan Davis who lived at Dahlonega, Georgia. "We

are getting along as well as we could under existing circumstances,"

Mary stated. "Have plenty of Yankees in this cove yet, and

we have got rid of some of our tory neighbors. The Yankees

took some of them to Chattanooga to give an account of their

behavior, and it is said they are after the others, but it

is most too good to be true. They paid us a visit last week

and took a few bushels of corn and we had a good quarrel,

and I told them good about their behavior. They were riding

Mr. Patton's horses -- two of them. O, how I wanted to kill

some of them. Times are pretty hot in this quarter; it is

reported that they had a fight about ten miles below here

yesterday, and we whipped them pretty badly, and captured

a good many prisoners, and I wish it had been the last one

of them."

"Mary

commenced writing," Julia Anne continued the letter, "but

I will finish. I received two letters from you a few days

ago. One was wrote last fall. You said something about the

money you owed me. I have no use for money, so don't trouble

yourself about it. I can't use what I have. We have troublesome

times in here. The Yankees is still gathering men, and carrying

them to Chattanooga. Some come back, while others go north.

Mr. Beard has just got back. They kept him two weeks. They

carried Lem McQuirter by here with five males and one horse,

and several other men I did not know. What few men there is

in here live in perfect dread. Mr. Whitlow slips in every

once in awhile. Saphronia thinks John had better not come

in here until after this fight is over. They commenced fighting

at Strudsles Shop and run them some way to Crawfish Spring,

others to Worthen's Gap. I look for hot times in here again.

I am much obliged to you for your invitation, but I think

we had better stay in here as long as we can. We have some

Yankee friends. We can buy parched coffee at 40 cents a pound,

bacon 12 cents, but we haven't bought any bacon. We have gardened

and planted potatoes. We can't keep a horse that is able to

work. If Johnson don't whip this fight we are ruined in this

country. Miz Howell is keeping school for us. Miz Johnson

has a good school in LaFayette, and Saphronia wants John to

bring Georgia Anna home to go to school when he comes. They

have taken some of the men that [had] taken the non-combatant

oath, and made then take the oath of allegiance. We are all

getting along very well, and I think John had better not come

in here until after he sees a little further, for he can't

do us any good. You must excuse this writing for I have not

time to write as Whitlow is a'going out. Write often. Give

my love to all, and accept a large portion for yourself. --

Julia."

The Davis Cemetery in 1986 (thanks to Vera Coulter)

The Davis Cemetery in 2002

After

the war John and Saphronia Davis continued to manage their

farm on West Chickamauga Creek. Similarly, Julia Davis and

her children maintained the old Martin Davis farm. Eventually,

many of them joined Martin in the cemetery at the orchard.

A descendant wrote the following description. "This spring,

1972, I visited the old home place of Martin and Julia Anna

at Davis' Cross Roads. Now it is Kensinton, Georgia. Here

on their farm is the Davis family cemetery. In an enclosure

of a wrought iron fence, surrounded by a rock wall you will

find the following graves: Bessie Perry Davis, born Dec. 27,

1883 died June 13, 1884; Parks Hall Davis, born Dec. 9, 1870

died Sept 12, 1871; Martin Luther Davis, born Beb. 8, 1879

died Dec. 8, 1879. All three children were the children of

John and Ruth Hall Davis. Martin Davis, born Aug. 27, 1809

died Nov. 11, 1859; Julia Anna Davis, born June 5, 1823, died

Sept. 28, 1882; Martin Davis Jr., born Sept. 23, 1856 died

Nov. 14, 1871. They have a small marker at each grave, and

a large monument about twelve feet high with all of Martin

Sr. family. It has four sides shaped something like a pyramid.

They call this place McLemore Cove, and it is a beautiful

site for a cemetery, tho, it needs a lot of work done on it.

Trees of cedar and oak etc. have grown up amongst the graves."

During the course of the present study, local informants explained

that the space between the wrought iron fence and the stone

wall at the cemetery contains un-marked graves of the Davis

slaves. The need for "a lot of work done on it" that Mattie

Davis noted in 1972 is much more apparent today. The trees

of cedar and oak that she found growing among the graves are

much bigger today. Smaller shrubs and brush fill in the spaces

between the trees to the point that the cemetery wall cannot

be seen from a few feet away. An old road trace was noted

on the west side of the cemetery.

References:

Official Records of the War of the Rebellion

Archive and files, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military

Park

Raymond Evans, The Civil War in Walker County

Significant

Views: There is a good view of the site at the intersection

of Highway 193 and Cove Road.

Setting:

The site is in a highly a rural setting. There are, however,

rumors of additional clear cutting that would seriously impact

of the visual nature of the area.

Documented

Structures, Sites and Features: The Julia Davis House

is still occupied and in good condition.

Presumed

Wartime Features: There was a significant battle on this

site on September 10 and 11, 1863. There could be numerous

Confederate and Federal campsites and other features in the

area.

Original

Terrain: The general terrain in the vicinity of this site

still retains much of its wartime condition.

Related

Sites: Widow Bailey's Crossroads, and Federal Earthworks.

|